Lynsey Calder: Printed Textile Designer

Exploring the culture of craft and making in Japan

Our long time collaborator and foundation trustee, Lynsey Calder, travelled to Japan in late 2023, where the focus was on expanding specialist knowledge in traditional textile techniques such as Indigo dyeing, katazome, and shibori.

As a lead technician in textiles at The Glasgow School of Art, Lynsey also aimed to strengthen relationships between academic institutions whilst being fully immersed in Japan’s rich culture of craftsmanship. We asked Lynsey a few questions about her trip to explore the unique experiences and insights gained in Japan. Our discussion touches on the thoughtful gifts exchanged with hosts, hands-on textile techniques practiced and detail on her recent project: recreating Bernat Klein’s iconic prints with modern technology.

What was the purpose of your recent trip to Japan?

My recent trip to Japan was a way for me to gather specialist textile knowledge, specifically around Indigo dyeing, katazome and shibori practices. I also wished to strengthen bonds between two art school institutions that have an exchange program with The Glasgow School of Art where I’m the lead technician in Textiles and also the print and dye technician for textiles. These were Kyoto Seika University in Kyoto and Tama Art University outside of Tokyo.

I also wanted to immerse myself in a culture that takes pride in and appreciates craft practices such as textiles, pottery, paper making and carpentry.

On your recent trip to Japan you gifted some Bernat Klein books to your hosts, what did you give them and why?

Yes, I gifted the recent Bernat Klein book which was published by the Bernat Klein Foundation to mark Klein’s centenary year in 2022. I would’ve liked to have also taken copies of Klein’s Eye for Colour and the Colour Guides but due to baggage allowances and travelling from place to place I had to leave these behind this time. It’s customary in Japan to offer a gift to your hosts and this was perfect in that it allowed me to spread the word of the exciting stories and life that were brought together by a diverse group of fantastic people touched by Klein in this beautiful book, it was a great gift and very well received. There is now a copy in the textile departments of both Tama Art University and Kyoto Seika University as well as with Bryan Whitehead at his silk worm farm in the mountains around Fujino. I’m very grateful to the Foundation for donating these books.

What techniques did you try during your visit to Japan?

Before I left for my trip I was sent a ‘homework box’ from Japan. This included instructions and materials for some quite complicated and time consuming shibori pieces and some stencil paper to create 4 hand cut stencils for resist printing onto fabric. So, the work started well before I departed Scotland. When I arrived at the Farmhouse for a 10 day intensive Japanese textiles course we were shown how to finish our pieces so that they could be dipped 10 times in indigo outside and then beaten in the river afterwards to remove excess dye. This resulted in some beautiful pieces of cotton and linen with varying geometric designs in blue and white. We were also shown how to make rice paste to push through our stencils to create a resist layer. Once the resist was dry we dipped these samples in indigo which gave beautiful sharp designs on the cotton cloth. In addition I tried printing with traditional hand cut stencils which portrayed designs which could’ve been decades old. It was an immersive and fun experience and I learned lot’s of new tips and tricks I didn’t know before.

Are these more traditional approaches than you would take in your printing practice?

I have always explored traditional techniques in tandem with innovative approaches to designing and making textiles. I don’t think the two approaches can survive without the other. Perhaps we use modern materials but process in the print room is still rooted in tradition. For example we use silk screens which have polyester mesh rather than silk which are exposed with light sensitive emulsion to create a permanent stencils, rather than hand cutting paper stencils which are used directly onto fabric with resist paste. Saying that we still use paper to create stencils in combination with screen which are very successful.

How would Klein have created his Diolen prints back in the 70’s?

Without going back in time and witnessing the full process behind Klein’s Diolen prints it’s very difficult for me comment with much confidence on how they were created exactly. It’s an area I’d like to do more research in. As yet I haven’t been privy to any examples of original design work for the prints apart from samples of finished fabrics either in a length or in garment form. It would be great to see original drawings, instruction, technical notes or photographs of production from the time. I believe that some of the designs are blown up photographs of flowers and there are prints which look like examples of Klein’s oil paintings. One of the larger pieces of fabric that I’ve been working from has what looks like glue dots along it’s selvedge which suggests it was either glued to a table or a roll for production. There is also a 5 colour key on the selvedge. This gives a lot of information. The print itself has some lovely examples of where colours have overlapped and created new colours. The Diolen fabric that I looked at for my project is a polyester based fabric which I imagine was printed with Disperse dyes which are specifically for synthetic fibres and are extremely durable, light and wash fast. This means that the vibrant colours have held up incredibly well for the last 50 years.

These may have been printed and heated to reveal the bright colours. These dyes are the same kind we use for sublimation heat transfer printing today.

How different was your process in recreating them?

When Bernat was creating printed textile designs from the late 1960s to the early 1980’s, the method he used was to enlarge photographic details of his original paintings. This was part of the textile designer’s process that used monologue photography as a way in which to create abstract shape and composition, a process inspired by his friend and fellow textile designer, Tibor Reich.

Although Bernat is the textile designer of the Diolen collection, the technical process of creating the repeating pattern for screen-printing would have been printed initially in Germany and later by Thomas & Arthur Wardle in Leek, Staffordshire. Bernat’s textile design would have been further developed into a repeating pattern, and then separated into individual colour and silk screens to produce a length of cloth.

In following this traditional method of silkscreen printing for textiles, my first priority was to ‘discover’ and recreate the original repeat design. This involved tracing individual colours from the original cloth design onto transparent layers to create each colour screen for textile printing. This allowed me to test my reconstruction of Bernat’s textile design.

My second phase in adapting Bernat’s textile design into a digital format, was to create a new version textile design that could more easily be reinterpreted. This was a detailed and lengthy process of preparation for printing onto natural fabric at The Centre for Advanced Textiles (CAT) based within The Glasgow School of Art.

Would there have been similar technical requirements/restrictions when he first created them to what you had to consider?

Although our current day processes for creating lengths of cloth can now incorporate monologue and digital methods, the same technical requirements and restrictions remain today. Our aim is always to print a length of fabric with as few mistakes and flaws as possible. The colour matching, finishing, light and wash fastness that were important and challenging in Bernat’s day, are still such an important factor for consideration by textile designers and producers.

Considerations of demand are required to ensure that fabrics are economical to produce yet special enough that the fabric and clothes are desirable. However, the innovation of digital print has created more bespoke opportunities for the production of luxurious printed fabrics and has opened up possibilities of the limited production of small runs on novel and diverse base fabrics.

In the period in which Bernat was practicing as a textile designer, his approach to printed textiles very much reflected the opportunities of that time. Bernat was invited to design for this new knitted jersey fabric, which allowed him to play with scale, colour and pattern. The screen-printing process was the ideal method in creating what have become known as Klein’s ‘Diolen’ Prints.

Explain why you had to approach them pixel by pixel?

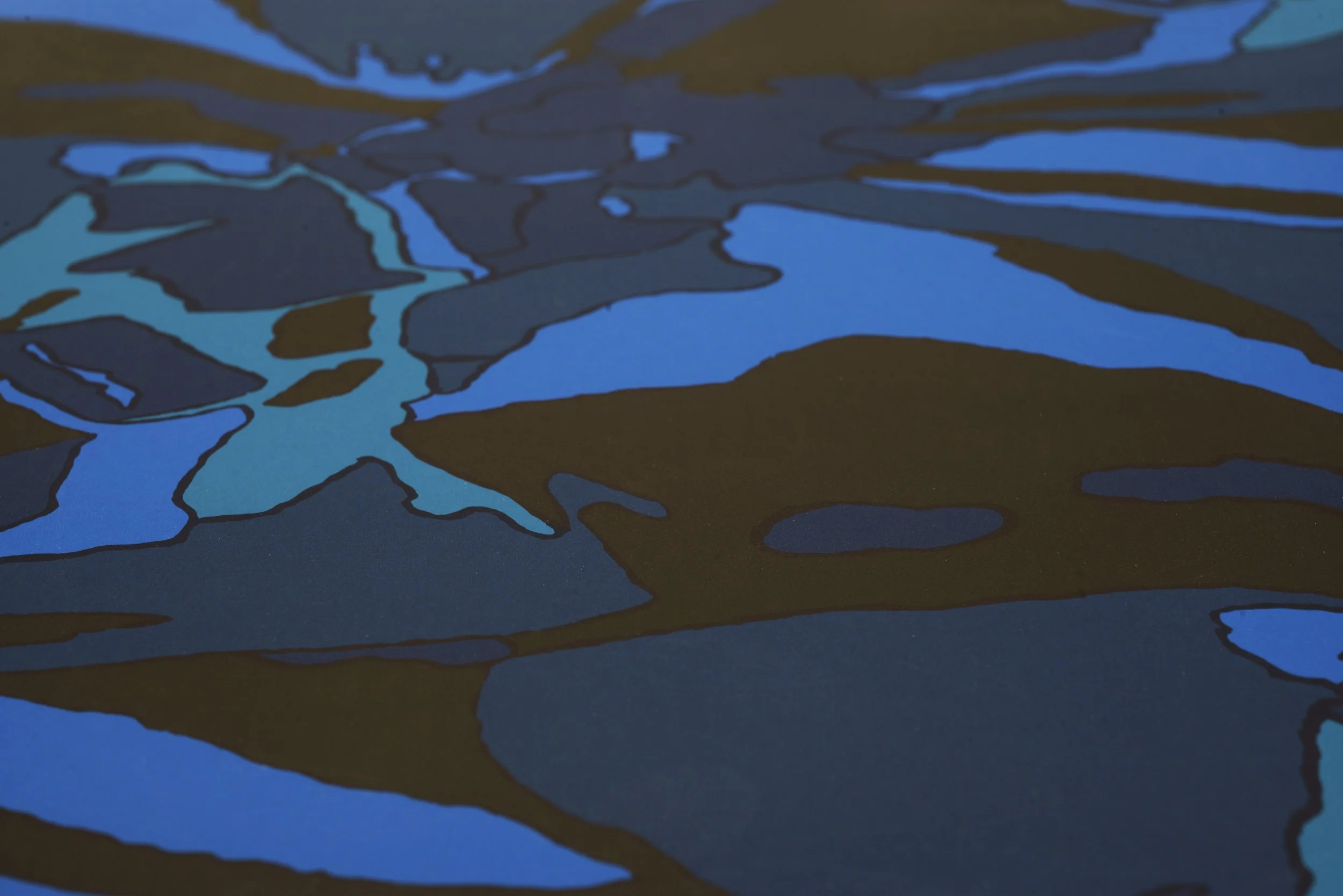

This was in relation to the information that I was attempting to translate from the original fabric. I decided to take photographs of the fabric I had and then imported them into Adobe Photoshop. To enable me to find and isolate the repeat pattern and then put that tile into a seamless repeat for digital print I also needed to remove all of the noise from the photograph and flatten the colours. This meant zooming in so that I could clean the edges between colours and create clean lines and re-draw in all of the areas of colour where there were overlaps. Due to the amount of texture picked up in a photograph resulting in millions of different coloured pixels I decided that I would follow the lines and clean each pixel to make clean lines. This allows for recolouring the pattern to be simpler in the long run.

What is your own personal feeling about the Bernat Klein Diolen prints?

I absolutely love the Bernat Klein Diolen prints. The colours are vibrant and fun and the differing scales of pattern in some of the examples I’ve seen are bold and brave. I believe that they have a timeless feel and are just as relevant now as when they were first produced.

What drew you to this project?

I was excited about the opportunity to work with The Bernat Klein Foundation to produce a creative outcome. I was able to really explore print again in the workshop in the way in which I was taught when I studied textiles over 20 years ago. Identifying a repeat pattern and then developing this through analogue and digital methods was an inspiring exercise which allowed me to get to know the prints intimately.

How would you like to see the final patterns developed?

I think that there is more to explore with the patterns. I’d like to elevate them further and look to designing a range of ‘Inspired By Klein’ patterns. Maybe limiting some of the parameters around the design and exploring colour palettes and pattern scale perhaps.

Through the delivery of the BKF workshop series to SME’s and practioners we were able to explore some interesting ideas around product and made to order meterage. I’d like the opportunity to develop the workshop series further and possibly identify routes for collaboration in the future.